The rise of love marriages? How market integration is changing how people marry in Matlab, Bangladesh

By Susie Schaffnit & Mary Shenk

Hollywood films portray marriage as a celebration of love between two people – a couple meets, falls in love, and then eventually gets married. Reality TV shows like Married at First Sight and Indian Match Making portray a different model of marriage. In this model, couples are paired by someone else and then married, with love maybe developing later, over time.

Though this model is portrayed as novel to Western audiences, for much of human history and in many places around the world today it is the norm for parents to arrange the marriages of their children, often with help from other relatives. Parents pick spouses for their adult children who will hopefully provide them a bright future. Parents increase their chances of arranging a ‘good’ marriage by investing in their children’s status – for example through education – and using whatever financial or social power the parent has to negotiate the marriages. Even so, sometimes parents and their children disagree over aspects of the marriage, for example spouse choice or timing. In these cases, parents usually have the power to override or convince their children to enter the marriage of the parents’ choice. But what happens when power-dynamics between parents and children change?

In a new paper published in Evolutionary Human Sciences, our research team set out to explore this question using data from Matlab, Bangladesh. Arranged marriages are very common in Matlab, but recently some people have started to participate in love marriages initiated by the marrying couple. Sometimes parents approve these marriages, creating what is locally known as an arranged love marriage, and sometimes parents don’t approve the match but the couple gets married anyway. Matlab is also undergoing rapid transition from people primarily practicing agriculture to greater integration into a market economy with many kinds of jobs, a process many anthropologists call market integration. This change has the potential to alter power-dynamics between parents and their children as children complete higher levels of education and take on jobs that contribute independently to their families’ wealth rather than mainly working in farming alongside their parents.

Our work set out to address several questions using data from 1598 married women from Matlab. We focused specifically on women as we have more detailed data on their marriages; women are also more likely to experience arranged marriages than men since in some cases marriages may be arranged for women but not for their husbands. We asked:

- How has the frequency of arranged versus love marriages changed over time?

- What are the characteristics of women who participate in arranged versus love marriages?

- How does market integration relate to patterns of arranged and love marriage?

Our analysis had four main findings:

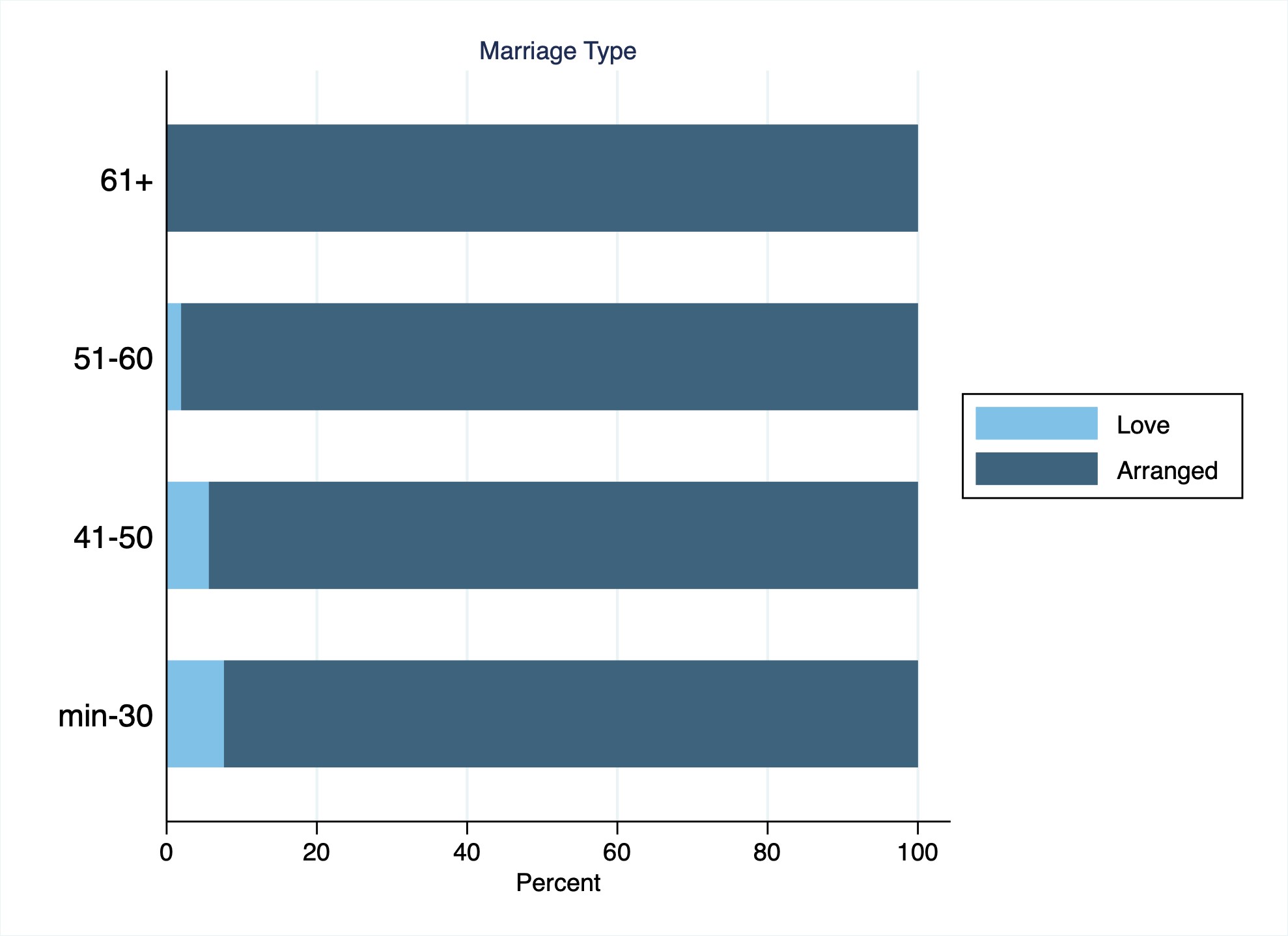

First, we found that love marriages have become more common in recent years. The vast majority of women (94%) in the study had arranged marriages. Love marriages, however, were primarily concentrated among younger women; with ¾ of all love marriages among participants younger than 36 years.

Second, we found that women in arranged marriages got married at younger ages and had less education than women in love marriages. The average age at marriage for those in love matches was a year older than those in arranged marriages, and they had just less than a year more education.

Third, we found that family-level market integration does not predict being in an arranged versus love marriage. We measured market integration of women’s families using information about women’s father’s occupation (e.g. agricultural work versus education-based work), but found that how market integrated a woman’s family was did not relate to the type of marriage she had.

Finally, we found that society-level market integration does seem to link to increases in rates of love marriage. Over the past few decades Matlab has undergone a remarkable amount of change as the process of market integration has occurred. This has not only impacted the jobs people do but has led to higher levels of education and later ages of marriage for men and women—with education and age at marriage linked since people usually finish their education before marriage in order to get a good job (mostly men) or a better position on the marriage market (both men and women). Such changes have had interesting consequences, including that:

- Young women are more likely to meet young men, i.e. potential spouses, by attending school for more years,

- Women’s higher education gives them status/power to choose a spouse separately from their parent’s status, and

- Women are older by the time they (or their parents) are ready to consider getting married and thus have greater autonomy should they disagree with their parents’ desires when it comes to marriage.

We argue that all of this together has led to a situation where women are less reliant on their parents to arrange a marriage and have greater opportunity to essentially arrange their own marriages, often with their parents’ approval but sometimes not.

The take home message is that increasing female education over the past few decades, a key accompaniment of market integration, is particularly important in opening the door to allowing love marriages in Matlab. Over time we thus expect that marriage decisions will increasingly being made jointly between parents and children as has been increasingly the case in urban regions of South Asia.